RGB

RGB is a spatial arrangement of nine cubes made of transparent material in the three basic colours – red, green and blue – and appropriate lighting. In the context of this exhibition the colours are symbols of Art, Science and Politics and the conviction of the curators that these represent a continuum of knowledge changing hues.

The object is a large-format interpretation of the additive method of colour mixing based on the physiological mechanism of human-eye reception. In a sense, it also refers to the beginnings of media, when the RGB model was first used in analogue technology. There are still monitors that work on the basis of the RGB light emission method.

The principal idea of the installation is to play in search of colour. Going through the maze of cubes, visitors can observe the colours permeating and mixing. The phenomenon is a result of interplay among the boxes and the small windows cut out in them. The resulting colour compositions observed by the viewers are different for different cubes. Moreover, by changing the angle of vision through the square hollows, the observer is guaranteed to discover new colour compositions.

RGB, 2015, D. Sobolewska / WRO Art Center.

Installation conceived by Dominika Sobolewska, realised together with Patrycja Mastej and Paweł Janicki, and produced by the WRO Art Center in Wroclaw, Poland.

More about the work on the artist's website.

The Inconvenient Tree

Our tree is inspired by the work of the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (see picture). It also makes reference to the ‘tree of life’ built for Milano Expo2015. It is an artificially built wooden tree, with branches representing continents or sub-continents. On each branch are hanging figures illustrating the imbalanced situation of access to food and water around the world. It is, basically, a different way of representing histograms or pie charts of data concerning this unbalanced situation in the world.

By consequence, if science asks to imagine how the ‘shape of the tree’ will be in 20, 30 … years, it is very hard to know how it will evolve. We would all dream of reaching a well-balanced situation by then, but the reality will certainly be different. It is indeed hard to estimate how cultural and religious habits, climate, and politics, will evolve and at what speed.

The questions that science poses are therefore very challenging: What will be the impact of research? What will be the impact of nutrition innovation? Of ‘functional’ food? Plant engineering? Personal dietary guidance? Reduction of food loss? Packaging? SMART agriculture? And so on…

The Inconvenient Tree, 2015, P. Loudjani.

Wooden artificially built tree sculpture designed by Philippe Loudjani.

The Maze of Knowledge

The Joint Research Centre possesses beautiful posters on various subjects treated in the past, e.g. on energy, eurocodes, etc., plus some scientific posters and, last but not least, the collection of posters made for its lunch time lectures. Putting them together gives an impression of the variety of work performed at the JRC.

Putting them in the form of a maze, then, would be a beautiful symbol of the difficulty of acquiring and disseminating knowledge. And maybe, this would slow down the people passing through the maze and push them to read at least the title. Or maybe something more?

The maze reflects the general difficulty of extracting knowledge from all the information glut wherein we live. It also reflects the fact that information is not open enough – certainly not open as it should, in an ideal world.

Maze of Knowledge, 2015, N. Spirito, F. Raes.

Installation conceptualised by Frank Raes, and designed by Nadia Spirito.

Geo-engineering

An artistic reproduction of a satellite image of the earth, a spot light that shines over it representing the sun… And floating umbrellas: they represent aerosols deployed by man in the higher atmospheric layers to reflect the light back to space.

This installation represents a satellite image made of bits and pieces of textiles, different in colour and texture, to convey an impression of the different uses man makes of the planet (forest, agricultural land, urban settlements, and water bodies). Umbrellas other than giving structure, colour and dynamics to the installation, should convey a sense of an artificial intervention on a natural system, in an attempt to modify a natural process to obtain the desired effect.

Should the effect of global warming and consequent climate change become unbearable, geo-engineering proposes to seed the higher atmospheric layers, the stratosphere, with aerosols that should reflect the sun light back to space. Or, alternatively, giant reflectors put in orbit should act in the same way. Other interventions, such as extraction of carbon from the atmosphere and storage underground or in deep sea, are also considered as Geo-engineering.

What remains unsolved is the side effect that such a human intervention can produce on the Earth System. We know the high level of interconnection that exists among the various elements, which make the Earth System: air, water, land and life. But we do not yet master the actual and complete workings of the complex connections between the various sub-systems.

Geo-engineering, 2015, S. Galmarini, G. Maenhout, N. Sacco.

Installation of a satellite image of the earth reproduced by Stefano Galmarini, Nicoletta Sacco and Greet Maenhout.

Soils

The installation aims to make people reflect on the relationship between soil and food production – in the main, an issue not at the forefront of an ever increasing urban population, whose sole contact with food is via supermarkets.

The centrepiece of the installation is a 5m x 5m wall panel, divided into areas that represent the main 'natural' constraints to the cultivation of arable crops. The size of each area on the panel is proportional to its extent on Earth (e.g. deserts occupy 18% of the terrestrial land mass, and 18% of the panel). Each area is filled with a photograph to represent the landscape.

In addition, the physical size of the panel represents the amount of fertile soil lost every second in Europe and about 1/4 of the amount of fertile soil per person on the planet. This means 252 ha/day or 1,000 km2 per year.

While the demands for food, animal feed and recently, biofuels, are all increasing, the amount of arable land (hectares) per person is falling. From around 0.52 ha per person in 1950 to 0.20 ha per person in 2010, or about 100 times the area of the 5m x 5m panel in this installation.

This puts increasing pressure on existing areas to produce crops and to convert natural/semi-natural habitats to agriculture. When soils fail so do societies. Just look at the consequences of events such as the Irish potato famine, the dustbowl of the mid-west in the 1930s or more recently, the Sahelian famine of the 1980s. In fact, the poor quality of land around much of the Mediterranean is the consequence of poor soil management in Roman times.

Soils, 2015, A. Jones.

Installation by Arwyn Jones.

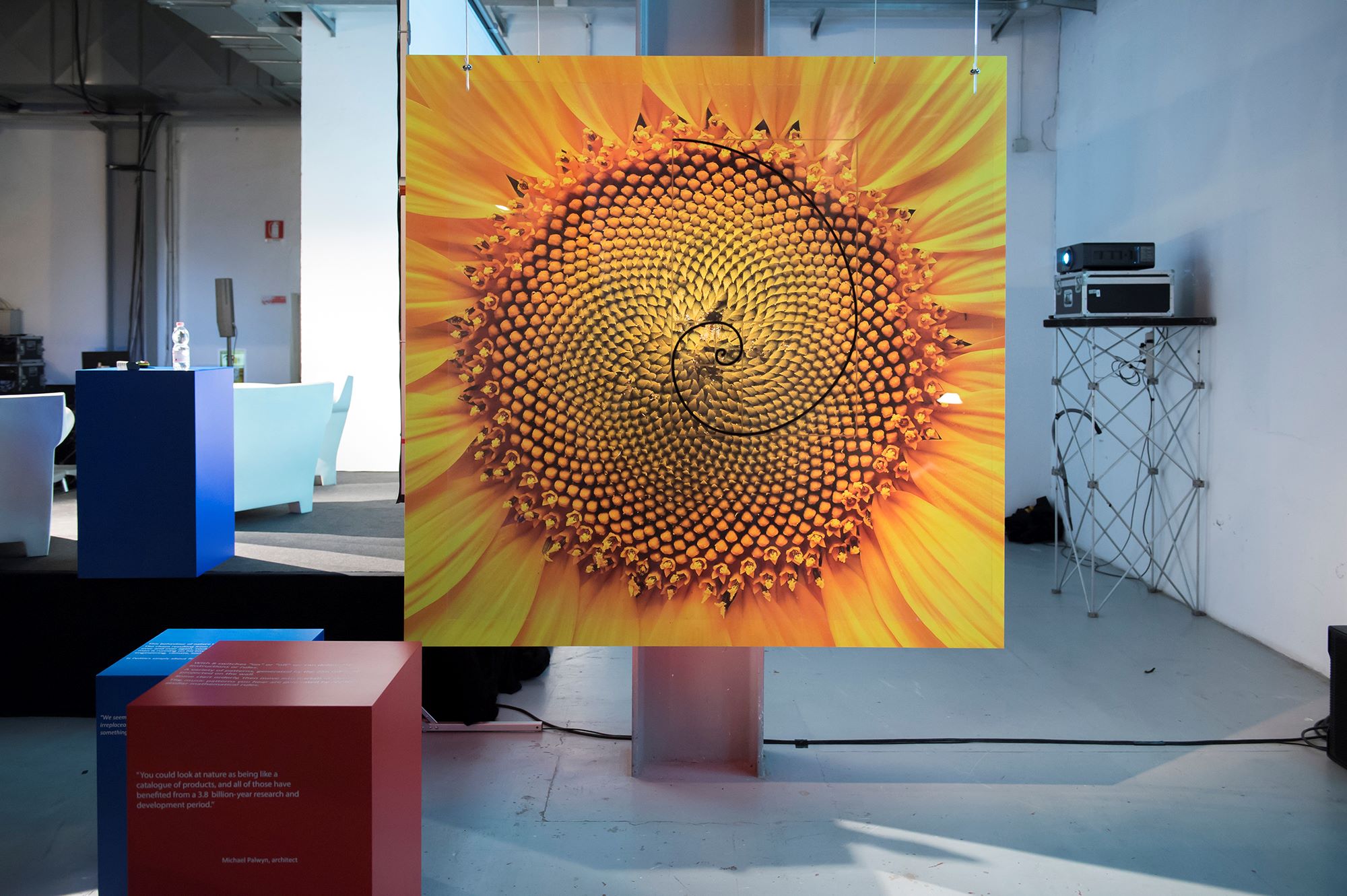

Mathematics of Nature

Seemingly complex and intricate patterns in nature are based on simple mathematical operations, applied over and over again.

The screen shows a so-called ‘Wolfram cellular automaton’. Cellular Automata (CA) consist of sequences of rows of black and white cells, where each next row is based on the configuration of the previous row, following a specific ‘rule’. The simplest CA sets the colour of a cell (black or white) depending on the colour of the 3 neighbouring cells in the previous row: the cell right above the new one, and the ones to the left and right. Because there are 2 possible states (black or white), there are only 8 possible sequences of black and white cells in a group of 3 neighbouring cells.

Another example of these patterns in nature is the Fibonacci sequence (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13,…), where each number is the sum of the 2 preceding ones. This sequence provides a simple mathematical framework for a wide collection of naturally occurring shapes and phenomena. Striking examples of the “Fibonacci spiral” are the Romanesco broccoli, the seed pattern arrangement in sun flowers, and pineapple and pine cone patterns. The number series also produces the ‘golden ratio’, already known by the ancient Greeks and Romans and re-discovered by the Renaissance. It was used by Le Corbusier and Salvador Dalì in their works; nowadays it is plentifully being applied in graphic design, architecture and music.

In this manner, the Wolfram cellular automata pose the question that occupies all of us: will we be able to control the changes into the earth system – or are we unwitting victims of societal laws of which we do not even know that they exist?

Mathematics of Nature, 2015, R. van Dingenen.

Installation by Rita van Dingenen.

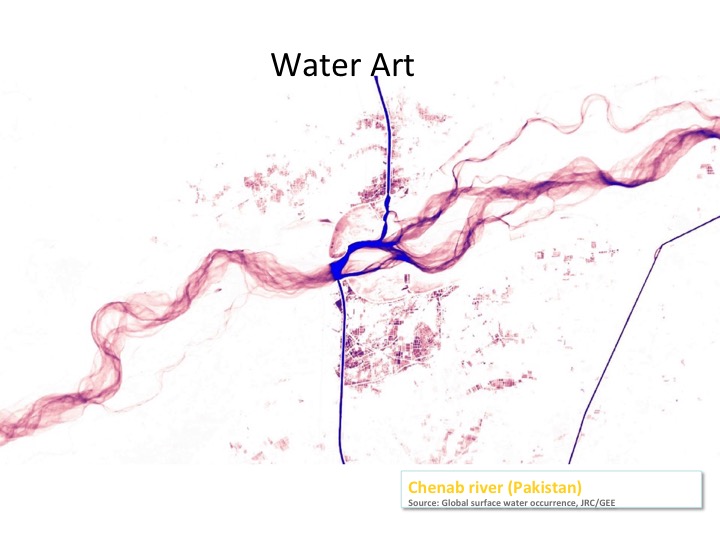

Mapping Water

This installation reveals the vivid and changing face of our planet’s water covering. Migrating rivers, shrinking and expanding wetlands, new coastlines, old coastlines, ancient meteorite impact craters, estuaries, mudflats, glacial melt lakes, rice fields and irrigation canals, salt ponds, fish ponds, new dams, old dams and the world’s great lakes underscore the beauty and fragility of our natural –and manmade- environment.

Water moves - we all instinctively know water flows downhill, but just think about the lakes that dry up (or have all the water extracted by humans), the rivers that change course, the coastlines that retreat (and advance) and the new lakes that come into being as dams are built or as rainfall increases, or glaciers and ice sheets melt. Our planet’s surface water covering is intensely dynamic.

And until now these dynamics have not been mapped. Where is Earth’s landmass permanently under water? Where are seasonal water-bodies found? When do they fill and empty? Where have new lakes formed and others emptied? Where do rivers move and where are they stable?

These new maps begin to answer the questions posed above. The first series of maps show the occurrence of water on our planet’s surface over thirty years, between March 1985 and March 2015. They have been created from more than 2.8 million satellite images acquired by the USGS/NASA Landsat programme (over 1000 terabytes of data).

Mapping Water, 2015, A. Belward, L. Demarchi.

Installation by Alan Belward, Andrew Cottam and Luca Demarchi.

Loop projection of movies of about 10 min showing elaborated Earth observations of water, water and and vegetation in RGB, with background music fitting the projections.

Animal Escape

The installation invites you to enter into a cage of 4 by 4 meters. It represents the cage of lab animals. Short cartoons and a movie introducing the basic scientific work are projected on various screens. A tower of Petri dishes represents the work of the toxicologists who are looking for alternative methods that will enable science to eventually do away with animal testing. The Petri dishes break through the top of the cage: that is the most realistic escape for animals. Microscope images of cells convey the beauty and complexity of living systems and the central role that cells play in developing alternative methods.

Animal studies do not always predict human outcomes: Both obvious and subtle differences between humans and animals, in terms of our physiology, anatomy, and metabolism, often make it difficult to apply data derived from animal studies to human conditions. New approaches using human cells in vitro and computer modelling can help us better understand how molecules interact with human biology:

Transitioning to new non-animal approaches is a win-win, avoiding animal testing while doing better science. Researchers spent decades infecting non-human primates with polio, and conducting other animal experiments, but failed to produce a vaccine. The breakthrough that led directly to the vaccine and a Nobel Prize, occurred when researchers grew the virus in human cell cultures in vitro.

The cage is a poignant reminder of the life lab animals have to bear. But it also points to aspects of sequestration that characterize contemporary society. Sequestration, in this sense, signifies a withdrawal into a false reality that is simply given. Animation has added a new dimension to the field of art and design. It reveals the invisible and makes the impossible possible. It is being recognised too as a powerful way of visualising, understanding and communicating scientific concepts and results. It is a perfect tool to give animals a personality, to convey the reality of animal use in science, and to introduce our work at the JRC in the "Three 3Rs" - to Replace, Reduce and Refine animal testing.

Animal Escape, 2015, R. Graepel, J. Triebe.

Installation by Rabea Graepel and Jutta Triebe.

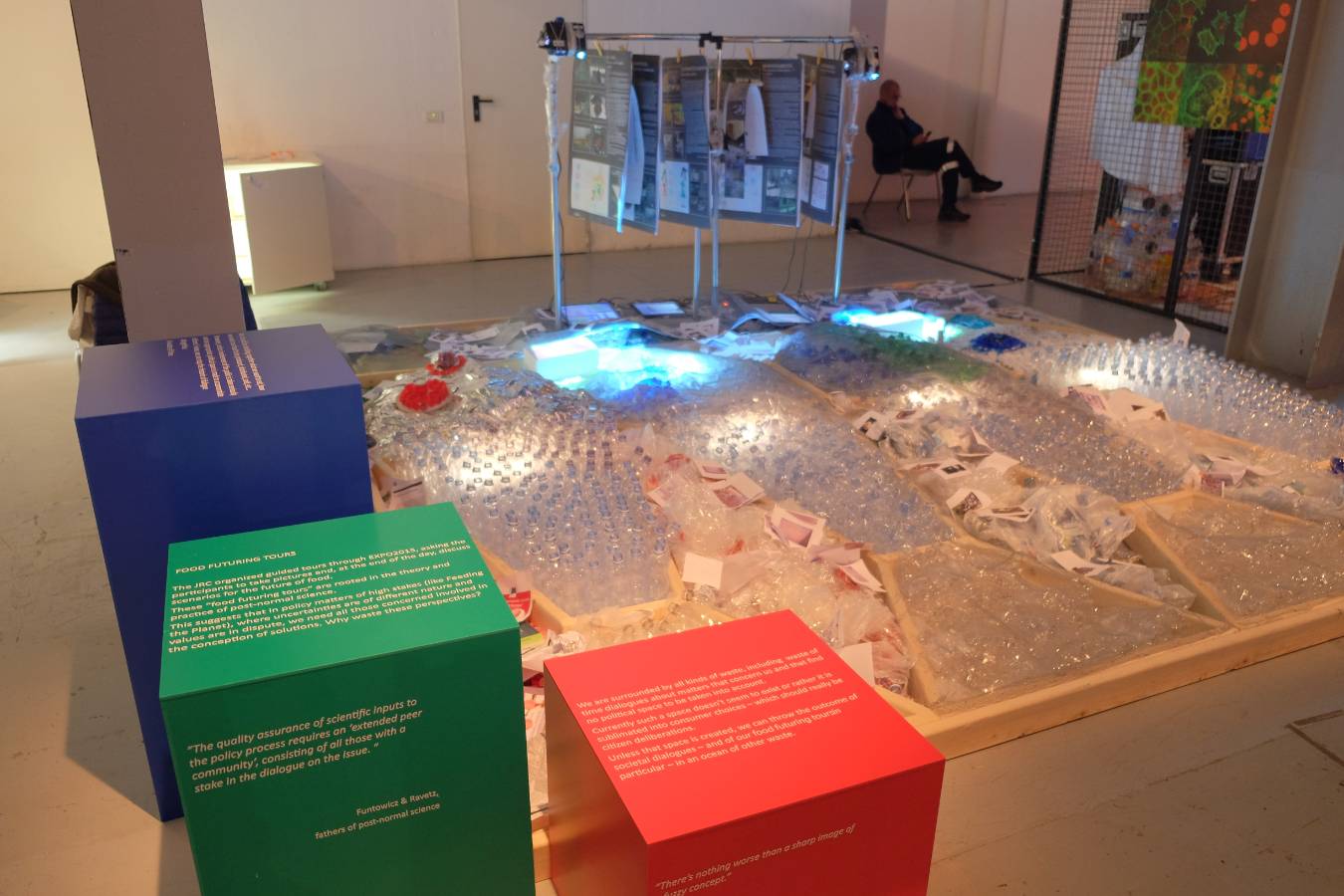

Food Futuring Tours

An installation centred on waste… of time, of resources, of ideas… At the same time it alludes to the waste generated by our food lifestyles, it also points to wasting the opinions and visions of the citizens about issues that matter to them.

The installation consists of ten scenarios about food futures narrated by the people that built them. They are presented amidst waste through posters in dry-clean racks and videos, which are projected in three different parts of an “ocean of waste. The fishes on the ground made of plastic waste represent what we ultimately feed the oceans with... The visitor is invited to feel and listen to the “ocean of waste” before arriving at another type of waste: visions of fellow citizens about food futures, wasted unless political space is found.

The background of this activity, called “Food Futuring Tours”, is a methodological experiment on “material deliberation”, a public engagement methodology recently developed at Arizona State University, with the participation of the JRC. The Food Futuring Tours invited participants to the Expo, where they were asked to record striking ideas on the possible futures of food. Any visual record was accepted, but most participants used digital photography on their smart phones. Starting point was the “food pasts” and “food futures”, displayed at chosen pavilions at the EXPO. Participants were then asked to engage in group conversations about the ‘food futures’ they imagined for 2040, focusing on the aspects identified during the walking tour, sharing their personal experiences and imagination.

Eighty citizens participated in this activity. In the encounters, ten scenarios were developed; ten storylines as narrated by the participants and illustrated with the photos they took. The resulting scenarios talk of co-existence, fusions, resilience, technology fixes, inequalities, messiness, consum-erism, conviviality – or, in other words, the different messages that foods have been carrying throughout times. In some sense, these scenarios are not utopias or dystopias, but they rather represent desirable or undesirable states.

Food Futuring Tours, 2015, Â. Guimarães Pereira.

Installation by Â. Guimarães Pereira.

Art in the Lab @ JRC

Since C.P. Snow’s The Two Cultures of 1959 provoked a heated philosophical debate in the UK and beyond, much has changed. From the establishment of Science and Technology Studies, the School of Edinburgh and the Sokal hoax, the discussion on art and science has most certainly entered a new era. Relationships between exact sciences and humanities, or between science and art, are undergoing considerable changes, not yet clearly mapped.

But at the JRC, we find many colleagues actively practicing an art, from theatre over painting and sculpture to writing and music. It seems appropriate to show these activities, and reflect on the mutations these borders have undergone and are undergoing in recent times – of which this festival is but a small expression.

If scientists are interested in art, it is not rare that considerations of influence and expediency move in. How to communicate hard data on global warming? How can a scientist discuss on the basis of unscientific proposals, e.g. as those made by climate deniers? By the evolution of science into a grey zone where science is denied by society, some scientists become activists to better defend scientific insights. Here too the borders between science and politics are not as clear-cut as we might wish.

Snow’s The Two Cultures was a passionate defence of a new education, where the rift between science and art might be overcome – his quote on science and art being sub-cultures indicates this clearly. How profound is this rift today? How can we overcome it? Can we provoke ‘A New Renaissance’ as the European Research Area Board advocates? In fact – can we still come up with something profoundly new? Where can we find those new ways of thinking that might help us, collectively, to tackle the great issues of our times?

Art in the Lab@JRC, 2015, JRC Scientists.

Different works of art by JRC scientists shown in a decor of vintage laboratory furniture.

The Living Room

A ‘continuous living room’ where the public can throw a look on the life of the writer and at the same time discuss the issues of the Resonances Festival. Open to all visitors, the Living Room welcomes all points of view, discusses perplexities, and enhances questions with new questions, all in a down-to-earth, amicable atmosphere where all opinions are allowed and all ideas can be followed. Wherever they may lead.

The Living Room find its origin in the Resonances workshop organised by the JRC in September 2015. It was an open space where artists, scientists and one politician met to discuss the possibilities of understanding and fertilising each other. The September-workshop was an important first step to understand the meaning of Resonance: resonance in the specific form of communication as dialogue, is not a perfectly symmetric relationship between sounds, as it can be in highly sophisticated stereo sound systems, but rather an echo – the emitted sounds return in a similar, more or less recognizable but slightly modified form.

It was that kind of dialogue we had between scientists, artists and one politician. Everybody had a basic idea of certain terms or words as resonance, sustainability, food, nutrition, environmental impact etc. We tried to explain to each other what might be the more specific meanings (“connotations”), from the point of view of the various “specialists” in their specific “field of sense”.

The Living Room, 2015, A. Schneditz.

Open space installation designed by Alf Schneditz.

FOOD | sustainable | DESIGN

An Eat Art performance with the aim to make people aware of the political and ecological consequences of food consumption. For this performance, Stummerer and Hablesreiter will force artists, scientists, and activists from various disciplines to cooperate with each other. The artist duo will set up a supermarket in the Superstudio and create a new set of ordering criteria for food presentation, based on, e.g. percentage of packaging, distance from the production site or the amount of water utilized for production.

The meal itself is an artistic intervention on the subject of value. The borders between art, science, and guests are completely removed: there is no stage, no panel, no auditorium. Everyone is in the same market.

FOOD | sustainable | DESIGN, 2015, Honey & Bunny.

Interdisciplinary performance by Sonja Stummerer and Martin Hablesreiter (Honey & Bunny).

More about the artwork on the artists' website.