A proposal for an immersive, interactive sound and light installation, controlled by the principles of the natural pollination system.

General Information

- Initiative

- Resonances IV NaturArchy

- Subject Matter

Biodiversity; complex systems; plant-pollinator-systems

- Lead Artist

- project owner test

Project Description

- Short description

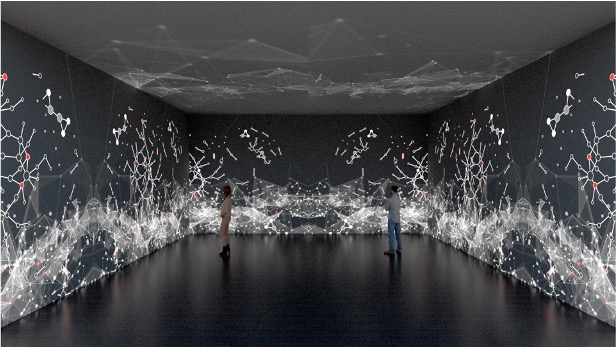

Anthos is an immersive, interactive sound and light installation that highlights the importance of pollinators and demonstrates our anthropocentric effect on them. With a goal to uncovering potentially hidden secrets about the plant-pollinator network and its functions, this installation is designed on the principles of complex theory. The final work will be an ever-changing data visualisation/sonification model of pollinator systems with audience input options. Participants inside this installation will affect how the network behaves — changing the audio and visual outcome.

- Full description of the artwork/installation

According to the global assessment on pollinators produced by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2016, seventy-five percent of our main food crops and nearly ninety percent of wild flowering plants depend to some extent on animal pollination for their reproduction. Beyond food, pollinators also contribute directly to the reproduction of plants used as medicines, biofuels, fibres like cotton and linen, and construction materials. It is indisputable that our human lives are intimately intertwined with the very special plant-pollinator network that hums in the background of daily life.

The majority of pollinator species are unmanaged, including more than 20,000 species of bees, many species of flies, butterflies, moths, wasps, beetles, but also birds, bats and other vertebrates. Currently, 16 percent of vertebrate pollinators, and more than 40 percent of invertebrate pollinators, are facing global extinction. Pollinators are increasingly under threat from human activities and countries must transform their relationship to pollinators if we are to turn the tide on biodiversity degradation.

There is rising attention on this topic from both the scientific communities and the European Commission, which are aiming to improve our knowledge and reverse the declining trend for pollinator populations. This serves as a driving force behind the creation of the artwork proposed in this project.

- Concept

Our proposal is to create an immersive, interactive sound and light installation that highlights the importance of pollinators, our anthropocentric affect on them, and uncover potentially hidden secrets about the complex plant-pollinator network and its functions.

- Scientific Background/Collaboration

Pollination is directly linked to human well-being through agricultural production and food security, but it is also crucial for the biodiversity of many natural ecosystems, as it regulates the reproduction process of both the crops we eat and wild plants. Pollination is a mutually beneficial interaction: plants have their pollen transported from their male reproductive organs (stamens) to the stigma of the female reproductive organs, and the animals, in turn, obtain food and resources in exchange for their services.

Around 75% of the main crops grown globally for human consumption rely to some extent on pollinators for the quantity and quality of their fruit and/or seed production5. These include crops grown in Europe, such as apples, berries, watermelons, tomatoes and oilseed, but also imported crops that form part of modern European diets, such as coconut, mangos, soybeans, cocoa beans and coffee. The expected direct reduction in total agricultural production in the absence of animal pollination ranged from 3% to 8%6. Pollinators also indirectly support meat, dairy and fish farming by pollinating crops used to feed animals7.

Pollinators improve not only the yield of many crops, but also the quality, in terms of fruit and/or seed yields, their nutritional content, and general appearance including fruit size. For example, insect-pollinated strawberries are bigger, redder, firmer and more flavoursome than strawberries that have been wind-or self-pollinated. They also have a longer shelf life and smoother shape. These pollinator-derived improvements increase the commercial grade of strawberries8.

Due to their importance for agriculture, pollinators have important consequences for livelihoods and national economies. Estimated global values of the crop pollination service range from 195 to 387 billion dollars annually (variations are due to methodology, assumptions and input data)9. These estimates represent the fraction of global food production attributed to animal pollination. However, pollinators provide many benefits to people beyond food, including medicines (e.g., allopathic and traditional herbal remedies), biofuels (e.g., canola and palm oil) and materials (e.g. cotton, linen and wood), which often have significant economic and aesthetic values.

Pollinators also play an essential role for global biodiversity. Nearly 90% of wild flowering plants depend at least to some extent on animal pollination - and around 50% of flowering plants are completely dependent on animal pollination, as they cannot self-pollinate10. In the absence of pollinators, there is a risk that many plants would not be able to adapt their reproductive methods, and would thus disappear. This would cause cascading effects within ecosystems and habitats worldwide, given the dependence of other animal species on the plants and habitats that pollinators help create11.

Numerous studies have highlighted a decline in wild pollinating species in Europe and around the world, in terms of abundance, diversity and spatial distribution. The available evidence is more than sufficient to trigger major concerns and urgent conservation action, given the critical role that pollinators play in supporting food production and underpinning ecosystems12.

There is no single overriding cause of wild pollinator decline, but multiple – likely interacting – factors, which can broadly be summarised as: land-use change, intensive agricultural management and pesticide use, environmental pollution, invasive alien species, pathogens and climate change. Current scientific opinion is that land-use change and land-management issues appear to be the most influential drivers of historic and ongoing pollinator biodiversity changes13. Land-use and land-management factors are especially significant as they remove or reduce the quality of habitats (destruction, fragmentation or degradation) and with that, the availability and quality of food, nesting and overwintering resources. However, the importance of a particular driver varies with geographical and ecological context, and with the pollinator species in question. This makes it very hard to universally rank the drivers on a quantitative basis, but it also shows why a richly diverse pollinator community of species is more resilient in the face of environmental change and shocks, such as climate change, habitat loss, diseases and pests. Indeed, species diversity supports effective pollination services as different species may be better at pollinating certain types of crop, or forage at different heights or in different parts of a field, in different sorts of weather, at different times of the year or day.

PLANT-POLLINATOR INTERACTIONS AS COMPLEX SYSTEMS

Plant-pollinator interactions do not occur in isolation but are embedded in complex interaction networks. Researching the intimate and intricate network of relationships in plant-pollinator communities holds the potential of understanding not only their functioning, but also our broad effects on such intricate systems, which is the result of co-evolutionary processes. Plant-pollinator interactions can be described referring to the theory of complexity14.

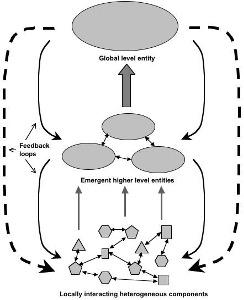

Fig. 2 A representation of a plant-pollinator network based on samples in a Mediterranean scrubland in GarrafNatural Park (Spain). Pollinator species are in orange, while plant species in green. Gray bar width denotes interaction strength, defined in terms of “encounters”, i.e. frequency of an individual pollinator visiting an individual plant It emerges that there are few very strong interactions and a large majority of weak interactions. Adapted from Figure 1 in Novella-Fernandez et al. (2019). 15 In general, a complex system is a collection of many components locally interacting with each other and with their environment. Through interactions, a complex system can spontaneously self-organise, producing collective behaviour without an initial plan and central authorities or leaders. There is no controlling entity, whether central or external, but 'control' is distributed among components and integrated through interactions between them. The properties of the whole system cannot be understood or predicted from the full knowledge of its constituents alone and their connections. In other words, 'the whole is more than the sum of its parts' and we can only observe the emergent behaviour of the system, produced by the interacting components. In nature, complex systems have multiple scales of organisation. Pollination systems can be illustrated as complex systems, whose components are pollinator and plant species, connected thanks to their mutually beneficial interactions. The complexity arises from several sources, including the sheer abundance of plants and pollinators (in both numbers and species), the richness of the interactions between individuals and populations of different species, the wide variations in environmental conditions that affect both organisms and their interactions16.

Fig. 4 The typical conceptual model of a complex system17 5 Klein A. M., et al. "Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops." Proceedings of the royal society B: biological sciences 274.1608 (2007): 303-313. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3721

6 Aizen M. A. et al. “How much does agriculture depend on pollinators? Lessons from long-term trends in crop production”. Annals of botany 103.9 (2009): 1579-1588. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcp076

7 IPBES “The assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on pollinators, pollination and food production.” (2016) https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3402856

8 Wietzke A. et al. "Insect pollination as a key factor for strawberry physiology and marketable fruit quality." Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 258 (2018): 197-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.01.036

9 Porto R. G. et al. “Pollination ecosystem services: A comprehensive review of economic values, research funding and policy actions.” Food Security 12.6 (2020): 1425-1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01043-w

10 Potts S. G. et al. "Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being." Nature 540.7632 (2016): 220-229. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20588

11 Christman, S.. "Do we realize the full impact of pollinator loss on other ecosystem services and the challenges for any restoration in terrestrial areas?." Restoration Ecology 27.4 (2019): 720-725. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12950

12 Science for Environment Policy “Pollinators: importance for nature and human well-being, drivers of decline and the need for monitoring.” Brief produced for the European Commission DG Environment. (2020)

13 IPBES “The assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on pollinators, pollination and food production.” (2016) https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3402856

14 De Domenico M. et al. “Complexity Explained” (2019). https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TQGNW

15 Novella-Fernandez R. et al. "Interaction strength in plant-pollinator networks: Are we using the right measure?." PloS ONE 14.12 (2019): e0225930. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225930

16 Bradbury, R. H., Green, D. G., & Snoad, N. (2000). Are ecosystems complex systems. Complex systems, 339-365.

17 Parrott, L. (2002). Complexity and the limits of ecological engineering. Transactions of the ASAE, 45(5), 1697. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.11032

- Additional context & background

In Michel Serres’ 1990 work Le contrat naturel, he discusses making peace with the world in order to save ourselves18. In order to make peace, we must first find a unified language in which to commune with nature. This project aims at finding this unified language through an extensive study of pollination networks, with a critical goal of extracting principles for the creation of a generative, interactive sound and light installation that amplifies this complex and yet fragile natural system.

As we look toward balancing the sheet on human/non-human relationships, it is critical that we examine the systems we are aiming to repair if we are to turn the tide on climate change and achieve the ambitious European Green Deal.

Visual Artist Giovanni Randazzo, Artist and Physicist Yiannis Kranidiotis, and Musician Sam Nester plan to work with Irene Guerrero Fernandez, PhD Ecologist with a focus on Farmland Biodiversity (JRC), Ana Montero Castaño, Wild Bee expert (JRC), and Alba Bernini, an expert in Complex Systems and mathematical modelling (JRC). The goals for this project are to:

- Conduct an in-depth research of the global pollinator-plant system

- Understand how human induced climate change is affecting the system

- Recognize the ways in which humans are dependent on the system (for food, agriculture, biodiversity, etc.)

- Build a model that represents these relationships in the form of an interactive, generative audio visual installation that demonstrates these principles.

Using principles of complex theory, the outcome will be an ever-changing data sonification model of pollinator systems with audience input options. Using Complex Explorables19 as inspiration, the final artistic product will allow participants inside this immersive installation to affect how the network behaves - changing the audio and visual outcome.

18 Michel Serres, Le contrat naturel, Paris, 1990, pg. 59

19 https://www.complexity-explorables.org/slides/jujujajaki-networks/

- Technical Framework

The final outcome for this SciArt proposal is to create an immersive, interactive installation. Visitors will enter a space in which the walls will be covered with visualisations of a digital model based on a complex system that demonstrates the plant-pollinator network.

The system controlling the space will calculate and generate visuals and audio in real-time as visitors explore the installation. An Infrared camera on the space's ceiling will track people's movement which will be translated into a heatmap that will affect certain parameters of the complex system being projected. These changes will be visible and audible to the audience. Designed to allow multiple participants inside simultaneously, their movement will be treated as the movement of a single organism (flock/hive). These may guide people to act as a group, taking collective decisions rather than moving as individuals.

Additionally, a CO2 and a temperature/humidity sensor will be placed inside the space, adding inputs for the digital model. These two parameters - CO2 and temperature/humidity - are essential in the pollination process.

Five projectors will be used to create the immersive visual field, covering the walls and ceiling of the space. Speakers at multiple levels will also be used to create a 3D sound experience. These visuals and sound will work together to enhance the visitor's experience and make clear the relationships between participants in the room and the system process. The IR camera on the ceiling will be connected to a central computer where custom-developed software will analyse the video and feed the algorithm of the digital complex system. The output of the system will be converted into visuals and audio inside the installation in real-time.

The minimum dimensions of the exhibition space for a true immersive experience are 8x8m. The installation can be adapted to different spaces as needed.

Budget

- Budget

EQUIPMENT QTY

UNIT PRICE

TOTAL

(€)

(€)

Projectors Epson EH-TW750 5

920

4600

Raspberry Pi Camera Module 5MP 160° (Fisheye) - Night Vision 1

50

50

IR Light LONNKY IR Illuminator Long Range up to 330ft/100m,30-LEDs 850nm,IR Infrared Light 1

90

90

HP Omen GT21-0016ng Intel® Core™ i7 i7-12700K 32GB DDR4-SDRAM 2000GB HDD+SSD NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 Desktop PC Windows 11 Home 1

2500

2500

MSI GeForce RTX 3080 12GB GDDR6X Suprim X LHR (4 outputs) 1

1200

1200

Active speakers, Genelec 8040 8

890

7120

Analog CO2 Gas Sensor (MG-811) 1

60

60

SHT35 Digital Temperature & Humidity Sensor 1

20

20

Arduino Uno 2

30

60

Raspberry Pi 4 / 4GB 1

120

120

Cables and electrical supplies -

300

300

Sound Card 1

1000

1000

Sound Software 1

1000

1000

GRAND TOTAL 18120

PLEASE NOTE: Artist fees have not been included in accordance with the guidelines.

Documents

PROCESS

The final outcome will be the result of a true collaboration between scientists and artists. The equal sharing of ideas, research, expertise, and data will guide the completion of this work from both sides.

JRC Residency One:

- During the first week-long residency at the Joint Research Centre in Ispra, the artists will undertake an in-depth study of historical pollination network models; research contemporary global issues surrounding human dependency on these networks; how our global climate crisis is affecting these networks; and what achieving the European Green Deal might look like for these networks. This research will be driven by Irene Guerrero Ferndandez and Ana Montero Castaño.

- Additionally, the artists will work with Alba Bernini in developing a computational model that is representative of the information studied.

JRC Residency Two:

- During the second week-long residency, the artists will work alongside Alba Bernini on refining the algorithmic principles of the digital model and begin prototyping visual and sound inputs, along with interactive audience technology. During this phase, a complete prototype of the digital programming will be finalised.

Post JRC Development

- Between completion of both residencies and final installation, the artists plan to work remotely, refining all digital inputs (sound and light design), and audience interactivity.

Links

- Redirect link